Celebrating the other D Days

The heroism of D Day should be remembered for all time, but there were other D Days during the Second World War that too should never be forgotten - D = Dad's (or in my case David's) Day.

Last week saw the 80th anniversary of the D Day landings, which reminded the world of the sacrifices that were made by our predecessors in carrying out that historic invasion.

It was right to mark that anniversary but the heroism at that time was only part of the huge sacrifice that was made during the war by so many to achieve the (more or less) lasting peace we have enjoyed ever since.

I was born after the war - just. Curiously I have to thank the Germans for the fact that I was born at all. Through my early childhood the talk among grown-ups and even four-year-olds was what happened and more particularly what our parents (mainly fathers) did in the war. Memories then were very raw. The country was in a state of shock. Rationing was still in place. My grandmother in Nebraska sent food parcels. My father talked about the war but not very often. I knew early on that he had been injured, had suffered a head injury that left him unconscious for a week. I asked him once if he had killed any Germans.

“Yes” he replied, and that was the end of the conversation.

Apart from being devoted to my mother, he was also a fanatical fisherman, a love that I certainly did not inherit. In later life he wrote a book - “Twice Hooked”. On the front of the dust cover was a drawing of a salmon leaping. When it was published, he gave me a copy. I politely thanked him but decided that I could read about the fish sometime later or even never.

Then recently (nearly 20 years after his death) I opened it and found - yes - too much about bloody fish, but in between the slimy creatures was the touching story of his wartime experiences and how the war brought him and my mother together - in Germany.

I wish now that I had read it when he was still around. I would have loved to find out more.

So here, heavily filleted are some extracts from Twice Hooked to celebrate D = Dad’s or David’s day and also all the other unsung dad-heroes who gave their all (and sometimes their lives) in the cause of a peace that has lasted more or less 80 years. Let us all try to make sure, despite the storm clouds on every horizon, that we keep it that way.

Here is what he wrote

For four years and six months they kept me away from 'England, Home and Beauty' (which is how we sadly referred to the place). No country except our own sent its soldiers away for such a period. A six year prison sentence, with remission, is less long and does not have the danger. For me, it was my twenty-third to twenty-sixth years, all gone beyond recall and not a thing to be done about it. There were times when the impossibility of getting home made me feel claustrophobic, frustrated beyond endurance; but even if one had the nerve and the genuine inclination, deserting in the Middle East was not an alternative. There were consolations, of course, the main ones being the daily, weekly and monthly feat of having survived. To these were added spells in the Canal Zone, where irrigation made life greener, and leaves in Cairo, where the shops brimmed with good things like Dunhill pipes and Rolex Oysters and where even a trooper's pay (£1.50 a week accumulated whilst in the desert) opened the doors to quite good eating places and bars

Most of all I was fortunate enough to sustain, early on, an injury that kept me away from the worst of the danger. The odds against a fighting soldier surviving four and a half years without being killed, severely wounded or captured, were no better than evens. My head injury was a blessing and I was lucky to have been singled out for it. When the brain began to clear, I found that I had been moved from the area of Tobruk to a base hospital that seemed like Eden.

As I walked from the ambulance to the tented ward a nursing sister muttered to her friend, 'Oh, poor boy'. It was lovely, a tiny bit of a hero at last. I realised that seven days had gone by and that I was wearing a beard on my juvenile features that might have affected a tender heart. While in this hospital I heard that in the next attack most of my squadron had been killed. Going back to the unit, or what was left of it, became even less attractive and (though I made the prescribed noises of frustration and disappointment) I was not sad when after some weeks in a convalescent camp in Palestine I was downgraded to B. That, fortunately, was a fairly honourable path away from the battles, because people with skull injuries did not thrive in I00° heat.

At that time I was a lance-corporal. Months passed, years passed, I had already decided that I would like to be an officer. Once again the machine took over and took me to Acre, the Middle East OCTU, from which I eventually emerged as a second lieutenant. There were still two years to go before my four and a half years were up. It had taken me nearly three years, from that awful night when I found myself in civilian clothes at Bovington camp, to get paid as a lance-corporal.

Then later

Going home on a troop ship filled with those who had also put in their four and a half years, every man and every woman a hardened soldier, was a stimulating experience. Of discipline there was little sign. My one night as Orderly Officer was a laugh a minute. My best moments were on the top deck one evening, with members of the Everton Supporters' Club (they had them in those days and each one of us on that boat deck was a highly potential hooligan). We had a quiz on the names of the grounds of other league clubs and I came out on top (even though I was, as they reminded me, a f ucking officer) when in the final round I named Elm Park as the home of Reading Football Club. I had imagined many times my return to that particular favourite haunt.

He was a football fan too, and supported Reading Town Football Club all through his life

I am no longer certain where we landed - it was probably at Plymouth. There was a crowded train journey - then we were launched into a strange and unwelcoming London. Why ever should there have been a welcome? People were coming back - as well as going·- all the time. Coming back was not much of a triumph - we were just lucky survivors, not dead, not maimed. We moved into the throngs of people, almost all in uniform, celebrating the fact that it was V.E. Day. Most people, men and women, were in uniform, the rest in the rather shabby formal clothes the war had left them. The atmosphere was like a return along Wembley Way after an English win - when there seemed no other means of celebrating than to jump and hug and sing. All the nation was having a fantastic party - but the nation knew each other. No one knew the passengers from the Middle East. I wandered around with the singing hordes - attempting to sing songs I had never heard before. One or two tentative approaches to passing young women were staunchly rebuffed. I ended up in a single bed in some military-type club and put in a 'phone call to my mother in Hampshire. The next morning I was on my way to Winchester, the Test, the Dever, the Itchen and some girlfriends - or widows - in that order. This was what I had really come back for. Elm Park would not be open for two months.

King and country gave me a lavish reward for my 4 1/2 years servitude, by forgetting about me. I was happily ignored by the War Office and my leave stretched from May until 18th December when, having dug out my battle dress, I set forth with a mixed crowd of fairly desolate soldiers for a posting to Germany. They had remembered that I'd once qualified as a lawyer and I was off to provide some legal services for which more than five years away from the law had left me unqualified.

A week or two later I had a letter from the War Office telling me that I would be joining the army of occupation in Germany as a legal officer. Three weeks later still came the news that I had to make my way to Munster leaving the UK on 18th December, a sensational date in my life for it had been on the 18th December 1940 that I had left Liverpool shivering for undisclosed destination in the hold of the ‘City of London’ accompanied by a battalion of other dispirited members of the royal tank regiment.

Going this time was very different. Germany was no longer a dangerous place. I travelled first class and even had my own issue camp bed though I do not think I took it with me. After a few days at Munster “learning the form”, they called it I was given the choice of posting between two places, one of which was detmold. Noticing the large scale map at least three promising rivers or streams I plumped for depth mode it was the most sensationally significant and brilliant choice of my life.

I moved into a pleasant mess surrounded by thoroughly laid-back people and eased myself into the duties of a legal officer. They were not too arduous. I had to learn the existing military law and apply it. The most public place where this happened was the Detmold Town court - the equivalent of a Magistrates Court though we do not sentence respectable ladies to three months in gaol for being out after curfew in our magistrates courts.

One evening I and two others from my best wandered aimlessly around to the officers club. A German band was playing a kind of dance music. On all customers on a raised. On a raised section at the far end of the room were three very senior officers indeed lieutenant- generals at the least - chatting up the loveliest girl I had ever seen. She was dressed in the smart eye-catching uniform of an American army captain. With no realisation of its significance, I turned to my mates and “that's the lady I'm going to marry”. It was the signal for another round of drinks and a lot of laughter and remarks like “she's a mile out of your league.”

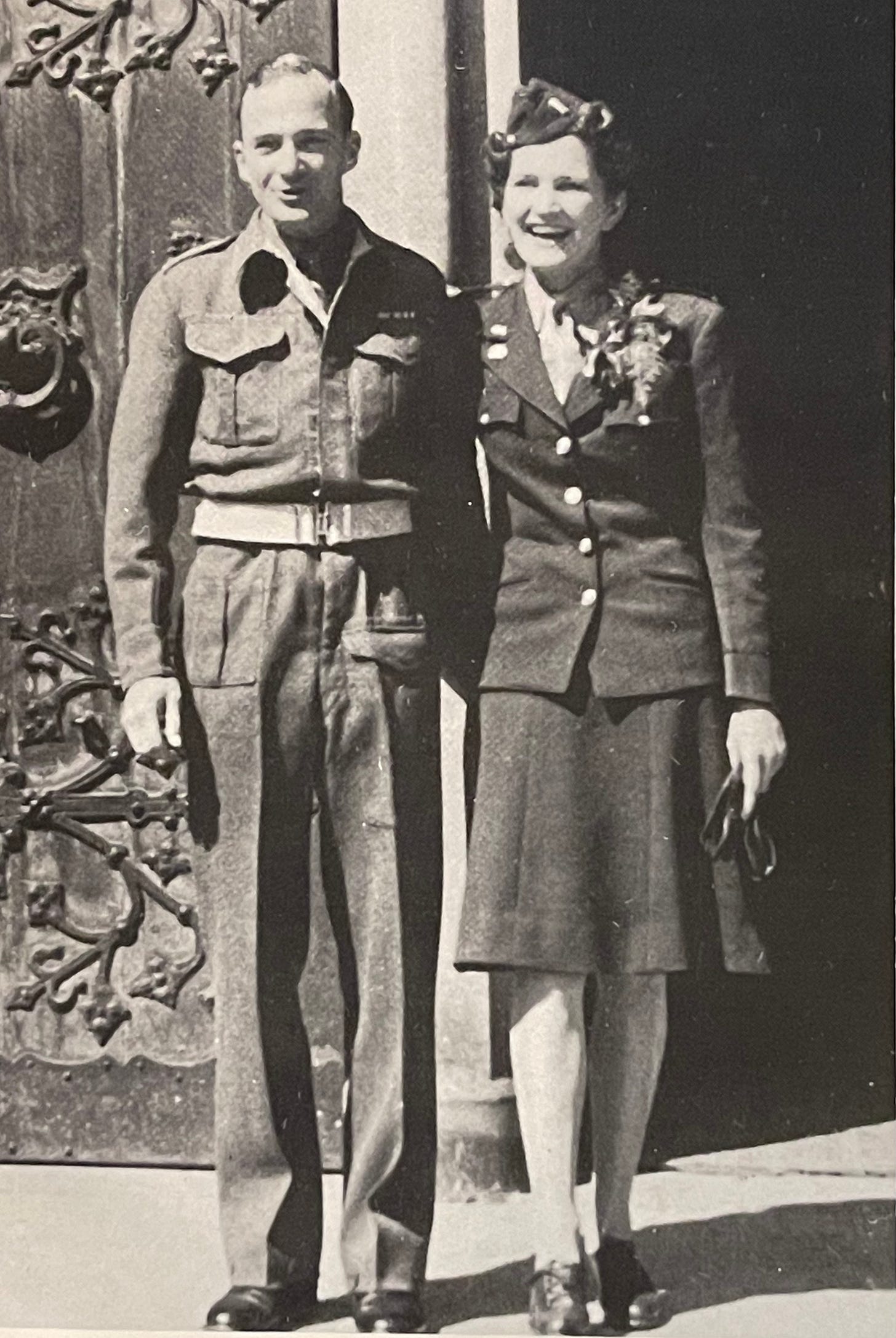

Yet, miraculously after eight hair raising weeks Marjorie and I walked up the aisle at the church at Detmold, the Movietone News cameras clicking (it was the first inter allied wedding in post war Germany) and all our friends assembled in optimistic surprise.

“Watch him” the best man had told her (Not without a touch of envy, for he too thought she was marvellous) but I can only say, as I near the end of this chapter that we have been magically happily married now for more than 44 years.

A little later in the book he gave more information about his American bride

Marjorie came from the Nebraska prairies where her family were farmers. During the depths of the depression she had worked away through university and medical school and got her MD. She gained a speciality in pathology, worked at Ann Arbor and then at Boston before joining the US army. At the time we met, she was in charge of the medical services in an enormous displaced persons camp near Detmold - and I was sending a number of her patients to prison for breaches of curfew.

What she liked much more than fishing were her horses. She had even taken one to the university with her (where she'd been offered a job in a circus) and through all our life together we have had horses as well as fishing. I don't horse. She doesn't fish. I help clean the stables in winter; in summer spring and autumn too - we take fishing holidays.

My family was entranced at the thought of the American doctor who was entering our lives. My mother was rehashing every medical symptom that she had suffered in the last five years, looking ahead to endless discussions over glasses of Sherry. The rest of the family were mildly reserved: what will the man do next they wondered? Marjorie's family had sent us a famous and a marvellous welcoming telegram on the wedding day but the letter from my mother-in-law (she had expected her daughter, naturally enough, to be practising in Nebraska) summed it all up “when I read your news I could have cried. I cannot bring myself to write any more”

She had previously met only one Englishman and he had disappeared with the forces Benevolent Fund that she had under her charge and thought that all Englishmen were of the same mould.

My grandmother was indeed pretty formidable. In the depression years her husband (my grandfather), overwhelmed by crushing debt, having been given the wherewithal by the quack doctor who was treating his depression and – so the story goes – was worried that he would not be paid his fee, committed suicide by slitting his throat. My grandmother saw off the creditors, kept and managed the family farm with her eldest son – and tried also to see off her new son in law to boot. The treatment that my grandfather received directly led to my mother training to be a doctor – because she felt she could do better. Indeed she could – and did.

Eventually my grandmother became reconciled to having an English son in law, but the food parcels continued to arrive long after rationing had ended in the UK.

Smile not simile!

What an absolutely beautiful story…such vivid memories written so beautifully…very poignantly too and I love the wedding photograph of your parents..what an absolute treasure your father’s book is